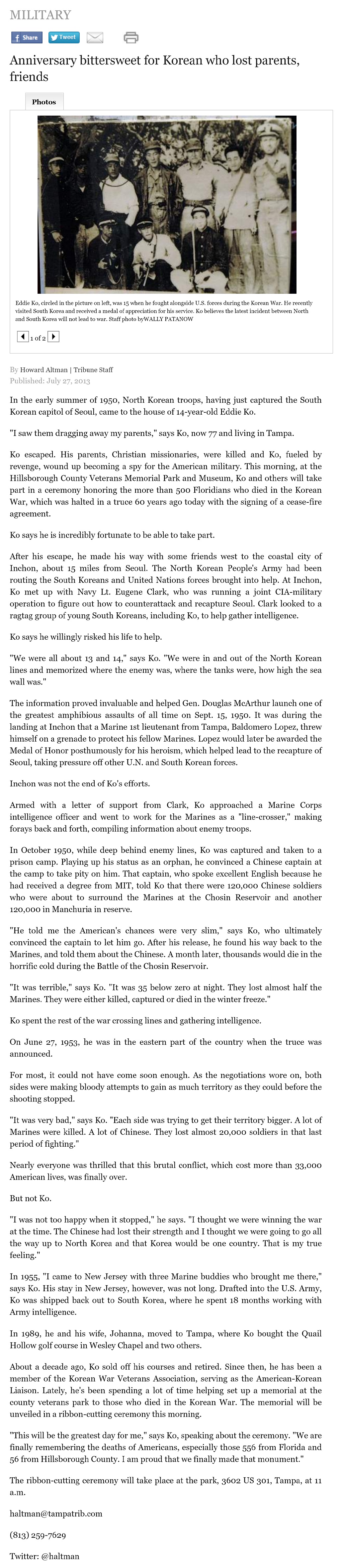

In the early summer of 1950, North Korean troops, having just captured the South Korean capitol of Seoul, came to the house of 14-year-old Eddie Ko.

“I saw them dragging away my parents,” says Ko, now 77 and living in Tampa.

Ko escaped. His parents, Christian missionaries, were killed and Ko, fueled by revenge, wound up becoming a spy for the American military. This morning, at the Hillsborough County Veterans Memorial Park and Museum, Ko and others will take part in a ceremony honoring the more than 500 Floridians who died in the Korean War, which was halted in a truce 60 years ago today with the signing of a cease-fire agreement.

Ko says he is incredibly fortunate to be able to take part.

After his escape, he made his way with some friends west to the coastal city of Inchon, about 15 miles from Seoul. The North Korean People’s Army had been routing the South Koreans and United Nations forces brought into help. At Inchon, Ko met up with Navy Lt. Eugene Clark, who was running a joint CIA-military operation to figure out how to counterattack and recapture Seoul. Clark looked to a ragtag group of young South Koreans, including Ko, to help gather intelligence.

Ko says he willingly risked his life to help.

“We were all about 13 and 14,” says Ko. “We were in and out of the North Korean lines and memorized where the enemy was, where the tanks were, how high the sea wall was.”

The information proved invaluable and helped Gen. Douglas McArthur launch one of the greatest amphibious assaults of all time on Sept. 15, 1950. It was during the landing at Inchon that a Marine 1st lieutenant from Tampa, Baldomero Lopez, threw himself on a grenade to protect his fellow Marines. Lopez would later be awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for his heroism, which helped lead to the recapture of Seoul, taking pressure off other U.N. and South Korean forces.

Inchon was not the end of Ko’s efforts.

Armed with a letter of support from Clark, Ko approached a Marine Corps intelligence officer and went to work for the Marines as a “line-crosser,” making forays back and forth, compiling information about enemy troops.

In October 1950, while deep behind enemy lines, Ko was captured and taken to a prison camp. Playing up his status as an orphan, he convinced a Chinese captain at the camp to take pity on him. That captain, who spoke excellent English because he had received a degree from MIT, told Ko that there were 120,000 Chinese soldiers who were about to surround the Marines at the Chosin Reservoir and another 120,000 in Manchuria in reserve.

“He told me the American’s chances were very slim,” says Ko, who ultimately convinced the captain to let him go. After his release, he found his way back to the Marines, and told them about the Chinese. A month later, thousands would die in the horrific cold during the Battle of the Chosin Reservoir.

“It was terrible,” says Ko. “It was 35 below zero at night. They lost almost half the Marines. They were either killed, captured or died in the winter freeze.”

Ko spent the rest of the war crossing lines and gathering intelligence.

On June 27, 1953, he was in the eastern part of the country when the truce was announced.

For most, it could not have come soon enough. As the negotiations wore on, both sides were making bloody attempts to gain as much territory as they could before the shooting stopped.

“It was very bad,” says Ko. “Each side was trying to get their territory bigger. A lot of Marines were killed. A lot of Chinese. They lost almost 20,000 soldiers in that last period of fighting.”

Nearly everyone was thrilled that this brutal conflict, which cost more than 33,000 American lives, was finally over.

But not Ko.

“I was not too happy when it stopped,” he says. “I thought we were winning the war at the time. The Chinese had lost their strength and I thought we were going to go all the way up to North Korea and that Korea would be one country. That is my true feeling.”

In 1955, “I came to New Jersey with three Marine buddies who brought me there,” says Ko. His stay in New Jersey, however, was not long. Drafted into the U.S. Army, Ko was shipped back out to South Korea, where he spent 18 months working with Army intelligence.

In 1989, he and his wife, Johanna, moved to Tampa, where Ko bought the Quail Hollow golf course in Wesley Chapel and two others.

About a decade ago, Ko sold off his courses and retired. Since then, he has been a member of the Korean War Veterans Association, serving as the American-Korean Liaison. Lately, he’s been spending a lot of time helping set up a memorial at the county veterans park to those who died in the Korean War. The memorial will be unveiled in a ribbon-cutting ceremony this morning.

“This will be the greatest day for me,” says Ko, speaking about the ceremony. “We are finally remembering the deaths of Americans, especially those 556 from Florida and 56 from Hillsborough County. I am proud that we finally made that monument.”

The ribbon-cutting ceremony will take place at the park, 3602 US 301, Tampa, at 11 a.m.