On a chilly Wednesday morning, Arlene Gillis arrives at the Tampa Jet Center toting a brown cloth bag containing a prosthetic leg and two prosthetic knees.

For most people, this would be unusual carryon luggage for a short flight to Tallahassee. But for Gillis, the devices, worth about $100,000 combined, are her stock in trade.

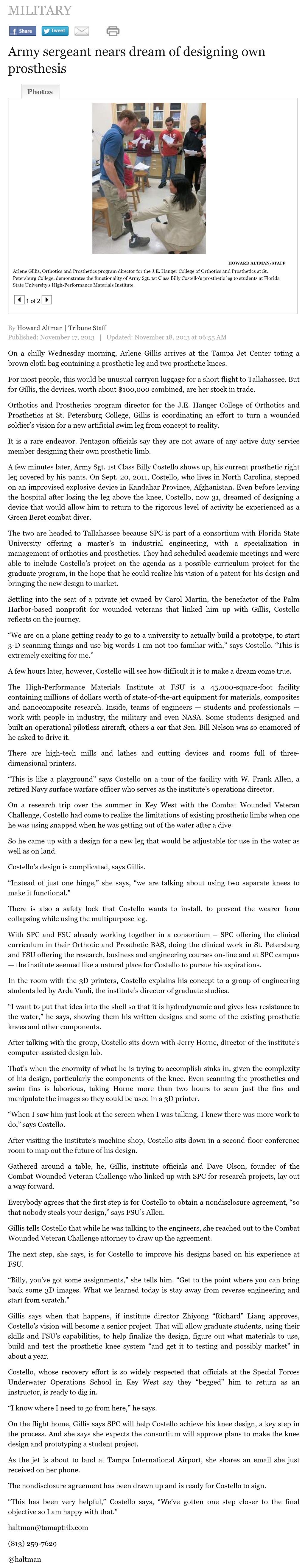

Orthotics and Prosthetics program director for the J.E. Hanger College of Orthotics and Prosthetics at St. Petersburg College, Gillis is coordinating an effort to turn a wounded soldier’s vision for a new artificial swim leg from concept to reality.

It is a rare endeavor. Pentagon officials say they are not aware of any active duty service member designing their own prosthetic limb.

A few minutes later, Army Sgt. 1st Class Billy Costello shows up, his current prosthetic right leg covered by his pants. On Sept. 20, 2011, Costello, who lives in North Carolina, stepped on an improvised explosive device in Kandahar Province, Afghanistan. Even before leaving the hospital after losing the leg above the knee, Costello, now 31, dreamed of designing a device that would allow him to return to the rigorous level of activity he experienced as a Green Beret combat diver.

The two are headed to Tallahassee because SPC is part of a consortium with Florida State University offering a master’s in industrial engineering, with a specialization in management of orthotics and prosthetics. They had scheduled academic meetings and were able to include Costello’s project on the agenda as a possible curriculum project for the graduate program, in the hope that he could realize his vision of a patent for his design and bringing the new design to market.

Settling into the seat of a private jet owned by Carol Martin, the benefactor of the Palm Harbor-based nonprofit for wounded veterans that linked him up with Gillis, Costello reflects on the journey.

“We are on a plane getting ready to go to a university to actually build a prototype, to start 3-D scanning things and use big words I am not too familiar with,” says Costello. “This is extremely exciting for me.”

A few hours later, however, Costello will see how difficult it is to make a dream come true.

The High-Performance Materials Institute at FSU is a 45,000-square-foot facility containing millions of dollars worth of state-of-the-art equipment for materials, composites and nanocomposite research. Inside, teams of engineers — students and professionals — work with people in industry, the military and even NASA. Some students designed and built an operational pilotless aircraft, others a car that Sen. Bill Nelson was so enamored of he asked to drive it.

There are high-tech mills and lathes and cutting devices and rooms full of three-dimensional printers.

“This is like a playground” says Costello on a tour of the facility with W. Frank Allen, a retired Navy surface warfare officer who serves as the institute’s operations director.

On a research trip over the summer in Key West with the Combat Wounded Veteran Challenge, Costello had come to realize the limitations of existing prosthetic limbs when one he was using snapped when he was getting out of the water after a dive.

So he came up with a design for a new leg that would be adjustable for use in the water as well as on land.

Costello’s design is complicated, says Gillis.

“Instead of just one hinge,” she says, “we are talking about using two separate knees to make it functional.”

There is also a safety lock that Costello wants to install, to prevent the wearer from collapsing while using the multipurpose leg.

With SPC and FSU already working together in a consortium – SPC offering the clinical curriculum in their Orthotic and Prosthetic BAS, doing the clinical work in St. Petersburg and FSU offering the research, business and engineering courses on-line and at SPC campus — the institute seemed like a natural place for Costello to pursue his aspirations.

In the room with the 3D printers, Costello explains his concept to a group of engineering students led by Arda Vanli, the institute’s director of graduate studies.

“I want to put that idea into the shell so that it is hydrodynamic and gives less resistance to the water,” he says, showing them his written designs and some of the existing prosthetic knees and other components.

After talking with the group, Costello sits down with Jerry Horne, director of the institute’s computer-assisted design lab.

That’s when the enormity of what he is trying to accomplish sinks in, given the complexity of his design, particularly the components of the knee. Even scanning the prosthetics and swim fins is laborious, taking Horne more than two hours to scan just the fins and manipulate the images so they could be used in a 3D printer.

“When I saw him just look at the screen when I was talking, I knew there was more work to do,” says Costello.

After visiting the institute’s machine shop, Costello sits down in a second-floor conference room to map out the future of his design.

Gathered around a table, he, Gillis, institute officials and Dave Olson, founder of the Combat Wounded Veteran Challenge who linked up with SPC for research projects, lay out a way forward.

Everybody agrees that the first step is for Costello to obtain a nondisclosure agreement, “so that nobody steals your design,” says FSU’s Allen.

Gillis tells Costello that while he was talking to the engineers, she reached out to the Combat Wounded Veteran Challenge attorney to draw up the agreement.

The next step, she says, is for Costello to improve his designs based on his experience at FSU.

“Billy, you’ve got some assignments,” she tells him. “Get to the point where you can bring back some 3D images. What we learned today is stay away from reverse engineering and start from scratch.”

Gillis says when that happens, if institute director Zhiyong “Richard” Liang approves, Costello’s vision will become a senior project. That will allow graduate students, using their skills and FSU’s capabilities, to help finalize the design, figure out what materials to use, build and test the prosthetic knee system “and get it to testing and possibly market” in about a year.

Costello, whose recovery effort is so widely respected that officials at the Special Forces Underwater Operations School in Key West say they “begged” him to return as an instructor, is ready to dig in.

“I know where I need to go from here,” he says.

On the flight home, Gillis says SPC will help Costello achieve his knee design, a key step in the process. And she says she expects the consortium will approve plans to make the knee design and prototyping a student project.

As the jet is about to land at Tampa International Airport, she shares an email she just received on her phone.

The nondisclosure agreement has been drawn up and is ready for Costello to sign.

“This has been very helpful,” Costello says, “We’ve gotten one step closer to the final objective so I am happy with that.”