Most weeks, Richard Cicero can be found spending an hour or two at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital, encouraging the wounded.

The 43-year-old, now living in Weeki Wachee, is uniquely qualified.

He has prosthetic devices where his right arm and right leg used to be, a story to tell about that, a son still in the service and an enduring spirit that pushes him to sky dive and shoot and live life to the fullest.

Tuesday, shortly after picking up an award from the Canadian military for saving the life of one of its soldiers, Cicero shared the advice he gives to the men and woman in hospital beds who wonder if they will ever be active again.

“It’s a matter of wanting to,” says Cicero, whose job was teaching soldiers how to spot and disarm improvised explosive devices (IEDs). “You have to want to, to succeed.”

Cicero’s life lessons began early.

“My father taught me how to shoot with both hands when I was young,” says Cicero, who would later follow his father, an officer with the Suffield, Conn., police department, into his own career in law enforcement. But first he did a stint in the Army as an intelligence analyst and communications sergeant who worked with special operations forces.

When his father, also named Richard, injured himself on duty while slipping on the ice, Cicero left the Army and took a job with a police department in Hamden, Conn.,

It was there Cicero says he was first introduced to working with police dogs, including the first dual purpose dog working with explosives. That led to a job with the Virginia State Police as a K-9 officer, where he worked from 2003 to 2007, until his right knee was injured by a dog that ran into him.

The injury was so bad Cicero says his knee was all but useless, propelling him into a job as a military contractor, working first with the Navy on combat skills and later with IED detection dogs. He made his first trip to Afghanistan in 2009, working with Marines in Helmand Province. He made a second trip in 2010, working with the Canadian military.

On July 31, 2010, Cicero was on foot patrol with a combat engineer team in Panjway District of Kandahar Province to clear the area of IEDs when all his years of training kicked in under great duress.

One of the Canadian soldiers, Cpl. Mark Hoogendoorn, “unfortunately found one the hard way,” says Cicero. He doesn’t like to talk about what happened next, saying “I just did my job.”

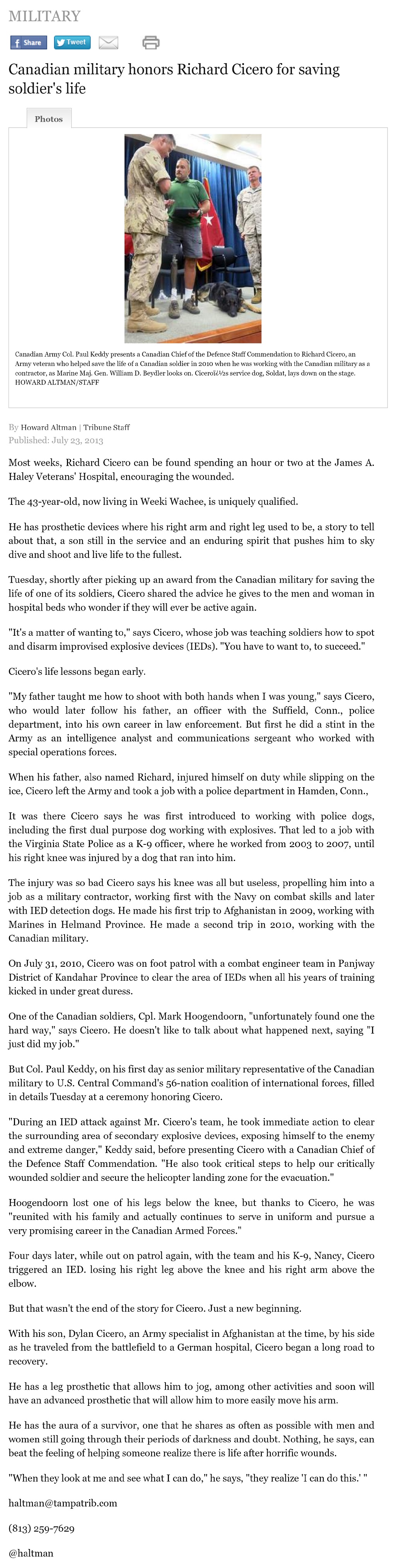

But Col. Paul Keddy, on his first day as senior military representative of the Canadian military to U.S. Central Command’s 56-nation coalition of international forces, filled in details Tuesday at a ceremony honoring Cicero.

“During an IED attack against Mr. Cicero’s team, he took immediate action to clear the surrounding area of secondary explosive devices, exposing himself to the enemy and extreme danger,” Keddy said, before presenting Cicero with a Canadian Chief of the Defence Staff Commendation. “He also took critical steps to help our critically wounded soldier and secure the helicopter landing zone for the evacuation.”

Hoogendoorn lost one of his legs below the knee, but thanks to Cicero, he was “reunited with his family and actually continues to serve in uniform and pursue a very promising career in the Canadian Armed Forces.”

Four days later, while out on patrol again, with the team and his K-9, Nancy, Cicero triggered an IED. losing his right leg above the knee and his right arm above the elbow.

But that wasn’t the end of the story for Cicero. Just a new beginning.

With his son, Dylan Cicero, an Army specialist in Afghanistan at the time, by his side as he traveled from the battlefield to a German hospital, Cicero began a long road to recovery.

He has a leg prosthetic that allows him to jog, among other activities and soon will have an advanced prosthetic that will allow him to more easily move his arm.

He has the aura of a survivor, one that he shares as often as possible with men and women still going through their periods of darkness and doubt. Nothing, he says, can beat the feeling of helping someone realize there is life after horrific wounds.

“When they look at me and see what I can do,” he says, “they realize ‘I can do this.’ “