Nearly four years after a bloody Afghanistan ambush that left five American troops dead, including the son of a Riverview woman, U.S. Central Command is still ensnared in an ongoing controversy of why it took so long to award a former Army captain a Medal of Honor for his role in that battle.

Last week, Centcom commander Gen. Lloyd Austin III, told a California congressman that he ordered a review of the medal-awarding process in Afghanistan. Problems with the process were discovered during a Department of Defense Office of Inspector General investigation into why it took so long for William Swenson to receive a Medal of Honor for which he was first recommended four months after the Sept. 8, 2009, ambush at Ganjgal Valley. Swenson was a captain at the time of the battle and has since left the Army.

In a letter to Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., the Inspector General’s office said its report found that while the head of U.S. forces in Afghanistan — at the time Army Gen. David Petraeus — properly endorsed Swenson’s original Medal of Honor recommendation, it was never forwarded to MacDill Air Force Base-headquartered Centcom, which oversees all military operations in the region.

Petraeus opted to downgrade Swenson’s award from a Medal of Honor to a Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest medal available to soldiers, and the awards packet was returned to the awards section for further processing.

There was no evidence that a senior office “mishandled, lost, destroyed, purged, disposed of, or unnecessarily delayed the recommendation,” according to inspectors.

But the investigation did find that the U.S. Forces-Afghanistan awards section “frequently lost awards, had unreliable processes and employed inadequate tracking systems. Those weaknesses likely contributed to its failure to both promptly forward the recommendations…and accurately track and report its status as a priority action.”

Centcom officials said it was too early in the review process to comment about how many awards might have been lost.

The letter, from Larry D. Turner, deputy assistant inspector general for communications and congressional liaison, concluded that Austin should direct a review of the awards process at U.S. Forces-Afghanistan “in order to prevent a reoccurrence of the problem in the future.”

Last week, Austin told Hunter that “award recommendations being misplaced or lost is unacceptable,” and ordered U.S. Forces-Afghanistan “to conduct a detailed review of their complete awards tracking process and report back to me with findings and recommendations.”

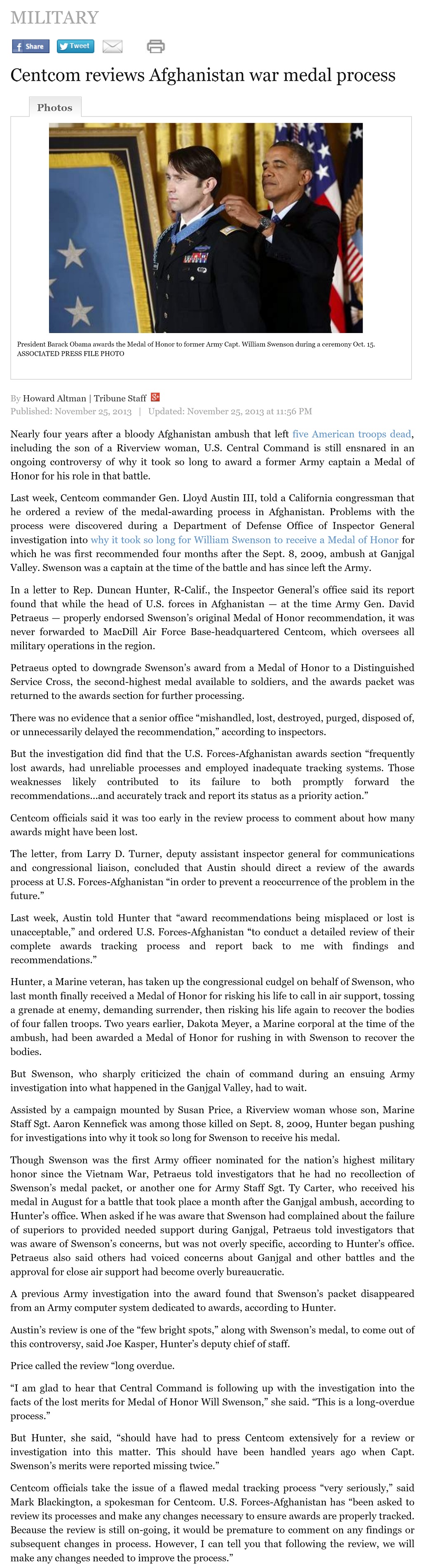

Hunter, a Marine veteran, has taken up the congressional cudgel on behalf of Swenson, who last month finally received a Medal of Honor for risking his life to call in air support, tossing a grenade at enemy, demanding surrender, then risking his life again to recover the bodies of four fallen troops. Two years earlier, Dakota Meyer, a Marine corporal at the time of the ambush, had been awarded a Medal of Honor for rushing in with Swenson to recover the bodies.

But Swenson, who sharply criticized the chain of command during an ensuing Army investigation into what happened in the Ganjgal Valley, had to wait.

Assisted by a campaign mounted by Susan Price, a Riverview woman whose son, Marine Staff Sgt. Aaron Kennefick was among those killed on Sept. 8, 2009, Hunter began pushing for investigations into why it took so long for Swenson to receive his medal.

Though Swenson was the first Army officer nominated for the nation’s highest military honor since the Vietnam War, Petraeus told investigators that he had no recollection of Swenson’s medal packet, or another one for Army Staff Sgt. Ty Carter, who received his medal in August for a battle that took place a month after the Ganjgal ambush, according to Hunter’s office. When asked if he was aware that Swenson had complained about the failure of superiors to provided needed support during Ganjgal, Petraeus told investigators that was aware of Swenson’s concerns, but was not overly specific, according to Hunter’s office. Petraeus also said others had voiced concerns about Ganjgal and other battles and the approval for close air support had become overly bureaucratic.

A previous Army investigation into the award found that Swenson’s packet disappeared from an Army computer system dedicated to awards, according to Hunter.

Austin’s review is one of the “few bright spots,” along with Swenson’s medal, to come out of this controversy, said Joe Kasper, Hunter’s deputy chief of staff.

Price called the review “long overdue.

“I am glad to hear that Central Command is following up with the investigation into the facts of the lost merits for Medal of Honor Will Swenson,” she said. “This is a long-overdue process.”

But Hunter, she said, “should have had to press Centcom extensively for a review or investigation into this matter. This should have been handled years ago when Capt. Swenson’s merits were reported missing twice.”

Centcom officials take the issue of a flawed medal tracking process “very seriously,” said Mark Blackington, a spokesman for Centcom. U.S. Forces-Afghanistan has “been asked to review its processes and make any changes necessary to ensure awards are properly tracked. Because the review is still on-going, it would be premature to comment on any findings or subsequent changes in process. However, I can tell you that following the review, we will make any changes needed to improve the process.”