News / Military

By Howard Altman / Tampa Bay Times / September 13, 2016

VIDEO: (missing)

With his A-4 Skyhawk shot out of the sky, Navy Lt. JG Bradley Smith plummeted to earth at 600 miles an hour. He hit the ejection lever just seconds before it was too late and wound up unconscious in a river in North Vietnam, surrounded by enemy dressed in black and toting AK-47s.

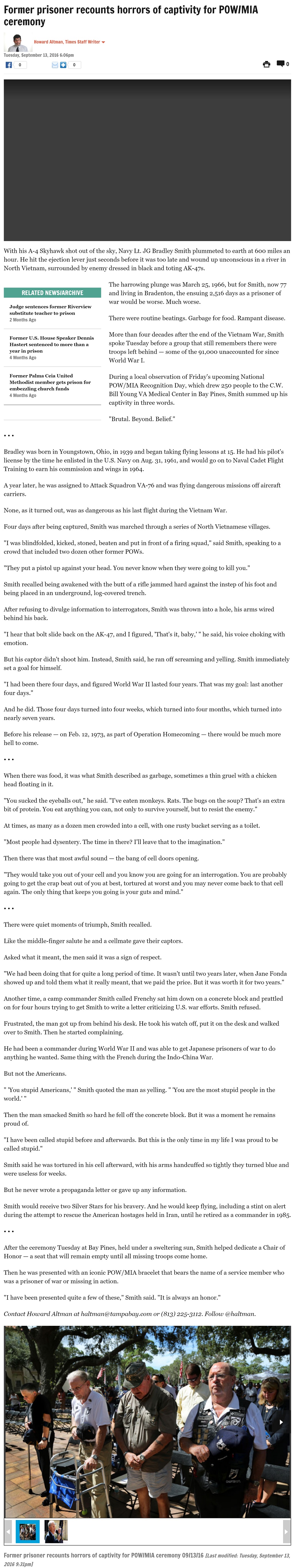

The harrowing plunge was March 25, 1966, but for Smith, now 77 and living in Bradenton, the ensuing 2,516 days as a prisoner of war would be worse. Much worse.

There were routine beatings. Garbage for food. Rampant disease.

More than four decades after the end of the Vietnam War, Smith spoke Tuesday before a group that still remembers there were troops left behind — some of the 91,000 unaccounted for since World War I.

During a local observation of Friday’s upcoming National POW/MIA Recognition Day, which drew 250 people to the C.W. Bill Young VA Medical Center in Bay Pines, Smith summed up his captivity in three words.

“Brutal. Beyond. Belief.”

Bradley was born in Youngstown, Ohio, in 1939 and began taking flying lessons at 15. He had his pilot’s license by the time he enlisted in the U.S. Navy on Aug. 31, 1961, and would go on to Naval Cadet Flight Training to earn his commission and wings in 1964.

A year later, he was assigned to Attack Squadron VA-76 and was flying dangerous missions off aircraft carriers.

None, as it turned out, was as dangerous as his last flight during the Vietnam War.

Four days after being captured, Smith was marched through a series of North Vietnamese villages.

“I was blindfolded, kicked, stoned, beaten and put in front of a firing squad,” said Smith, speaking to a crowd that included two dozen other former POWs.

“They put a pistol up against your head. You never know when they were going to kill you.”

Smith recalled being awakened with the butt of a rifle jammed hard against the instep of his foot and being placed in an underground, log-covered trench.

After refusing to divulge information to interrogators, Smith was thrown into a hole, his arms wired behind his back.

“I hear that bolt slide back on the AK-47, and I figured, ‘That’s it, baby,’ ” he said, his voice choking with emotion.

But his captor didn’t shoot him. Instead, Smith said, he ran off screaming and yelling. Smith immediately set a goal for himself.

“I had been there four days, and figured World War II lasted four years. That was my goal: last another four days.”

And he did. Those four days turned into four weeks, which turned into four months, which turned into nearly seven years.

Before his release — on Feb. 12, 1973, as part of Operation Homecoming — there would be much more hell to come.

When there was food, it was what Smith described as garbage, sometimes a thin gruel with a chicken head floating in it.

“You sucked the eyeballs out,” he said. “I’ve eaten monkeys. Rats. The bugs on the soup? That’s an extra bit of protein. You eat anything you can, not only to survive yourself, but to resist the enemy.”

At times, as many as a dozen men crowded into a cell, with one rusty bucket serving as a toilet.

“Most people had dysentery. The time in there? I’ll leave that to the imagination.”

Then there was that most awful sound — the bang of cell doors opening.

“They would take you out of your cell and you know you are going for an interrogation. You are probably going to get the crap beat out of you at best, tortured at worst and you may never come back to that cell again. The only thing that keeps you going is your guts and mind.”

There were quiet moments of triumph, Smith recalled.

Like the middle-finger salute he and a cellmate gave their captors.

Asked what it meant, the men said it was a sign of respect.

“We had been doing that for quite a long period of time. It wasn’t until two years later, when Jane Fonda showed up and told them what it really meant, that we paid the price. But it was worth it for two years.”

Another time, a camp commander Smith called Frenchy sat him down on a concrete block and prattled on for four hours trying to get Smith to write a letter criticizing U.S. war efforts. Smith refused.

Frustrated, the man got up from behind his desk. He took his watch off, put it on the desk and walked over to Smith. Then he started complaining.

He had been a commander during World War II and was able to get Japanese prisoners of war to do anything he wanted. Same thing with the French during the Indo-China War.

But not the Americans.

” ‘You stupid Americans,’ ” Smith quoted the man as yelling. ” ‘You are the most stupid people in the world.’ “

Then the man smacked Smith so hard he fell off the concrete block. But it was a moment he remains proud of.

“I have been called stupid before and afterwards. But this is the only time in my life I was proud to be called stupid.”

Smith said he was tortured in his cell afterward, with his arms handcuffed so tightly they turned blue and were useless for weeks.

But he never wrote a propaganda letter or gave up any information.

Smith would receive two Silver Stars for his bravery. And he would keep flying, including a stint on alert during the attempt to rescue the American hostages held in Iran, until he retired as a commander in 1985.

After the ceremony Tuesday at Bay Pines, held under a sweltering sun, Smith helped dedicate a Chair of Honor — a seat that will remain empty until all missing troops come home.

Then he was presented with an iconic POW/MIA bracelet that bears the name of a service member who was a prisoner of war or missing in action.

“I have been presented quite a few of these,” Smith said. “It is always an honor.”

- Photo 1: Vietnam veterans David Miller, from left, Larry Caldwell, Don Liston and John Harrison rise for the benediction during Tuesday’s POW/MIA remembrance at the C.W. Bill Young VA Medical Center. (DOUGLAS R. CLIFFORD | Times)

- Photo 2: Retired Navy Cmdr. Bradley Smith, 77, was a prisoner for 2,516 days — nearly seven years.

Wayback image