Arch Bush, now almost 91 and living in Sun City Center, says he has no special plans in store for today.

Ed Bialy, 88, says he may wander over to the local VFW post in Brooksville, for some hot dogs and beer.

Maurice Johnson, 90, says he will continue an annual tradition, dinner with friends at their Lakeland home.

The three men, who never met, share a bond that fewer and fewer will ever know.

On the morning of June 6, 1944, they were among about 156,000 Allied troops taking part in Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy.

Setting off from Eng�land in the pitch black, Bush, Bialy and Johnson crossed the Channel to France in landing craft, buffeted by rain and rocked by heavy seas. They survived German artillery, mortars, mines and underwater barricades in the greatest amphibious assault in history.

Every day, the ranks of those who set out to liberate Europe that day are thinned as time catches up with the Greatest Generation.

All told, about 16 million Americans served in WWII, according to the National WWII Museum in New Orleans. Little more than a million are still alive.

Every day, more than 500 WWII veterans die, according to the museum.

“That’s natural,” says Bush, who joined the CIA after the war. “I am going to be 91 soon. That means I am nearing the end and a lot of my friends are doing the same thing. We don’t have any control over it.”

❖ ❖ ❖

In the early hours of the sixth day of the sixth month of the 44th year of the 20th century, Arch Bush was a 20-year-old Navy corpsman, sitting aboard a hulking gray vessel called alanding ship, tank. Slightly longer than a football field, it could carry about 20 tanks or more than 200 troops.

Bush was on a ship full of tanks. Its mission was to deliver the armor to a swath of the 50-mile invasion front called Omaha Beach, which, along with Utah Beach, was one the two areas to be assaulted by Americans. Two other sections, Gold and Sword, were attacked by the British while the Canadians landed on Juno.

After off-loading the armor, the ship was to be converted into an emergency evacuation vessel, taking wounded off the beach and back to Eng�land.

As he waited to depart, the battle was already underway. There had been a long deception campaign to throw the Germans off. Waves of planes were pounding enemy positions and about 13,000 paratroopers and 4,000 more in gliders were already behind German lines.

“We were on a little stream on the south coast of England,” Bush says. “We were waiting for many weeks. We left and it was dark, couldn’t see anything.”

By the time the big ship made it out into the Channel for the 110-mile journey, “we could gradually see hundreds of other ships moving in the same direction,” Bush says.

❖ ❖ ❖

There were about 5,000 ships that left from Eng�land that morning.

Ed Bialy was steering one.

He was 18 and fearless as he clambered aboard thelanding craft, mechanized, a 56-foot-long boat with a ramp in front.

A Navy petty officer third class, Bialy had joined his new unit, which had come to England from North Africa, as a replacement.

Taking off from Plymouth, it was Bialy’s job to get the 75-ton vessel across the Channel to Utah Beach, the northern-most point of the Allied landing, selected to help secure the nearby port of Cherbourg.

“It had two diesel engines,” Bialy says. “Each was 225 horsepower. It had twin screws. It could move.”

❖ ❖ ❖

Hunkered down in the 114-foot-long vessel known as a landing craft, tank, 20-year-old Pfc. Johnson made the crossing with his platoon of Army combat engineers and a load of about seven or eight trucks.

“I never saw so many vessels in one place before then or after,” Johnson says. “We were not bombed on our way in. The Germans had fortified the area, south of where we were. Yes, there were people shooting at us, but not many, because there weren’t many Germans behind.”

❖ ❖ ❖

Omaha was “the most restricted and heavily defended beach” of the five invasion areas, according to a U.S. Army history of the invasion:

Omaha Beach was unlike any of the other assault beaches in Normandy. Its crescent curve and unusual assortment of bluffs, cliffs and draws were immediately recognizable from the sea. The high ground commanded all approaches to the beach from the sea and tidal flats. … Any advance made by U.S. troops from the beach would be limited to narrow passages between the bluffs. Advances directly up the steep bluffs were difficult in the extreme. German strong points were arranged to command all the approaches and pillboxes were sited in the draws to fire east and west, thereby enfilading troops while remaining concealed from bombarding warships. These pillboxes had to be taken out by direct assault. Compounding this problem was the allied intelligence failure to identify a nearly full-strength infantry division, the 352nd, directly behind the beach. It was believed to be no further forward than St. Lo and Caumont, 20 miles inland.

“As we gradually moved closer and closer to the coast, I could hear firing,” Bush says. “I could see battleships firing. As we got close, I could see dead Americans in their life vests, floating in the water.”

From the distance, Bush says, he could see the beach. A short while later, the LST hit the shore, lowered its ramp and the tanks onboard rolled off.

“I don’t remember being scared,” Bush says. “I had a job to do.”

As soon as the armor left the ship, Bush says he began cleaning the deck.

“We had to get ready for the wounded,” he says.

❖ ❖ ❖

Utah Beach was added to the initial invasion plan almost as an afterthought, according to the Army history:

The allies needed a major port as soon as possible, and Utah Beach would put VII (U.S.) Corps within 60 kilometers of Cherbourg at the outset. The major obstacles in this sector were not so much the beach defenses, but the flooded and rough terrain that blocked the way north.

For those headed to Utah, the approach was still deadly.

On his way to the beach, Bialy says he couldn’t understand the big water spouts kicked up all around him.

“‘What the hell is going on?’ he recalls thinking, finding out later that it was the Germans’ 88 mm artillery shells exploding all around him.

Just getting to the beach was dangerous, Bialy says, “because of all the things the Germans had submerged in the water.”

There were steel beams welded together, he says, “designed to rip the hull of incoming boats,” and other obstacles.

“There are ramps to flip the boats over, to steer them into mines,” he says. “Then there was another one, Rommel’s Asparagus, with tiller mines. There were iron frames 10-feet high.”

Utah Beach, Bialy says, was flat, and behind it, there were “big sand dunes with a few bunkers” full of Germans.

“They kept shooting,” Bialy says. “Everything. They had mortars, all the big artillery stuff like that. And we were shooting back.”

Bialy recalls feeling shock waves travel through the air as the 16-inch main guns of the USS Texas opened up on German positions.

Despite everything, Bialy and his four fellow crew members, along with a boat full of troops, safely made it to shore, where the ramp lowered and the soldiers made their way onto the beach. Bialy says he doesn’t know what happened to them.

The ramp went back up and the boat made its way toward docked ships, where it picked up supplies, making about four round trips back to the beach that day. The risk was increased by one crate that stayed on the whole time, 1,500 pounds of TNT for the engineers.

“You are 18 years old,” Bialy says, who drove a tractor-trailer after the war. “You do not fear death at all. You just go and do your job.”

❖ ❖ ❖

By the time Johnson hit Utah Beach, 40 minutes into the invasion, German resistance there had collapsed to the point where he wasn’t on the sand for long.

“I crossed Utah Beach and headed inland and I never saw the beach again,” he says. “We were only on the beach for about 15 or 20 minutes.”

His platoon’s first order of business “was taking care of roads, removing debris and mine sweeping so the roads could be used,” he says.

That first day, his platoon made it about a mile inland, suffering no casualties.

❖ ❖ ❖

After the vehicles rolled off the LST, corpsman Bush started sweeping off the tank deck in anticipation of the wounded arriving.

It didn’t take long, he says, before amphibious vehicles began showing up with men cut down by the German defensive barrage.

There were men who were shot. Hit by shrapnel. Torn up by artillery.

“I was down on tank deck dealing with wounded,” Bush says. “There were about 10 of us doing this, just going from stretcher to stretcher to see how I could be helpful. We gave them water. Made them comfortable. Those with abdominal wounds needed to have them cleaned. It was very rudimentary. Men died on the way back to England.”

All told, more than 9,000 Allied troops were killed or wounded in Normandy that day, the Army says.

❖ ❖ ❖

Ed Bialy will talk about the old times today with fellow veterans, none of whom were on Normandy.

Maurice Johnson will continue his tradition of celebrating the day with friends.

Arch Bush says he will stop and think a bit and get on with his day.

“The friends I had when I was in the Navy are all gone,” he says. “I am the lone survivor. I can talk to other people, but no one who was with me in the Navy at any point.”

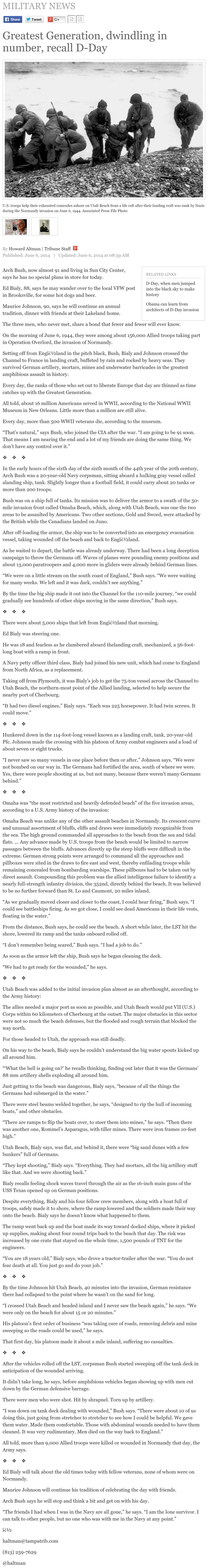

PHOTO1:U.S. troops help their exhausted comrades ashore on Utah Beach from a life raft after their landing craft was sunk by Nazis during the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944. Associated Press File Photo