News / Military

About 50 of the 74 surviving medal winners are expected to attend the annual convention to talk about service, sacrifice and lessons learned. Kids are their target audience.

By Howard Altman / Tampa Bay Times / January 9, 2019

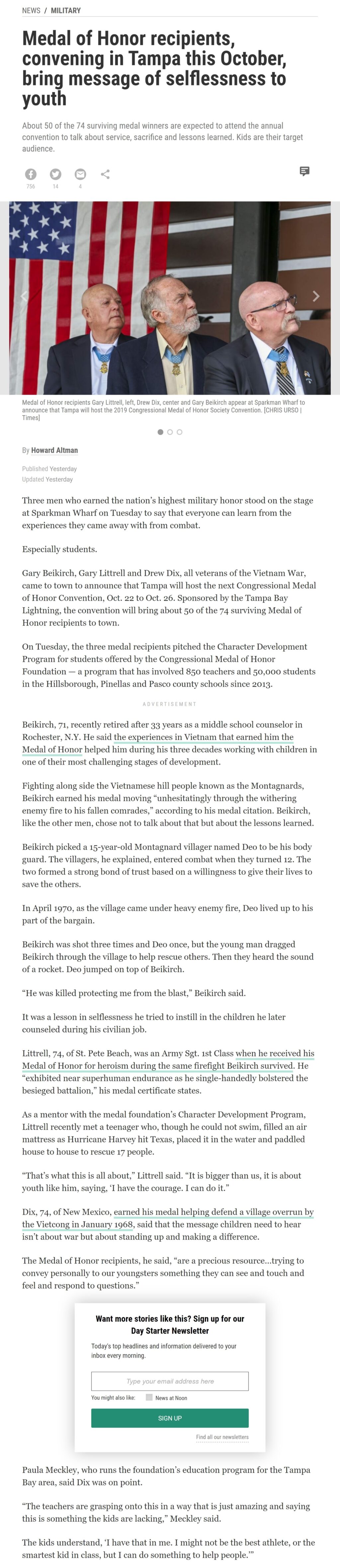

PHOTO: Medal of Honor recipients Gary Littrell, left, Drew Dix, center and Gary Beikirch appear at Sparkman Wharf to announce that Tampa will host the 2019 Congressional Medal of Honor Society Convention. (CHRIS URSO | Times)

Three men who earned the nation’s highest military honor stood on the stage at Sparkman Wharf on Tuesday to say that everyone can learn from the experiences they came away with from combat.

Especially students.

Gary Beikirch, Gary Littrell and Drew Dix, all veterans of the Vietnam War, came to town to announce that Tampa will host the next Congressional Medal of Honor Convention, Oct. 22 to Oct. 26. Sponsored by the Tampa Bay Lightning, the convention will bring about 50 of the 74 surviving Medal of Honor recipients to town.

On Tuesday, the three medal recipients pitched the Character Development Program for students offered by the Congressional Medal of Honor Foundation — a program that has involved 850 teachers and 50,000 students in the Hillsborough, Pinellas and Pasco county schools since 2013.

Beikirch, 71, recently retired after 33 years as a middle school counselor in Rochester, N.Y. He said the experiences in Vietnam that earned him the Medal of Honor helped him during his three decades working with children in one of their most challenging stages of development.

Fighting along side the Vietnamese hill people known as the Montagnards, Beikirch earned his medal moving “unhesitatingly through the withering enemy fire to his fallen comrades,” according to his medal citation. Beikirch, like the other men, chose not to talk about that but about the lessons learned.

Beikirch picked a 15-year-old Montagnard villager named Deo to be his body guard. The villagers, he explained, entered combat when they turned 12. The two formed a strong bond of trust based on a willingness to give their lives to save the others.

In April 1970, as the village came under heavy enemy fire, Deo lived up to his part of the bargain.

Beikirch was shot three times and Deo once, but the young man dragged Beikirch through the village to help rescue others. Then they heard the sound of a rocket. Deo jumped on top of Beikirch.

“He was killed protecting me from the blast,” Beikirch said.

It was a lesson in selflessness he tried to instill in the children he later counseled during his civilian job.

Littrell, 74, of St. Pete Beach, was an Army Sgt. 1st Class when he received his Medal of Honor for heroism during the same firefight Beikirch survived. He “exhibited near superhuman endurance as he single-handedly bolstered the besieged battalion,” his medal certificate states.

As a mentor with the medal foundation’s Character Development Program, Littrell recently met a teenager who, though he could not swim, filled an air mattress as Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, placed it in the water and paddled house to house to rescue 17 people.

“That’s what this is all about,” Littrell said. “It is bigger than us, it is about youth like him, saying, ‘I have the courage. I can do it.”

Dix, 74, of New Mexico, earned his medal helping defend a village overrun by the Vietcong in January 1968, said that the message children need to hear isn’t about war but about standing up and making a difference.

The Medal of Honor recipients, he said, “are a precious resource…trying to convey personally to our youngsters something they can see and touch and feel and respond to questions.”

Paula Meckley, who runs the foundation’s education program for the Tampa Bay area, said Dix was on point.

“The teachers are grasping onto this in a way that is just amazing and saying this is something the kids are lacking,” Meckley said.

The kids understand, ‘I have that in me. I might not be the best athlete, or the smartest kid in class, but I can do something to help people.’”

Wayback image