News / Military

By Howard Altman / Tampa Bay Times / June 24, 2016

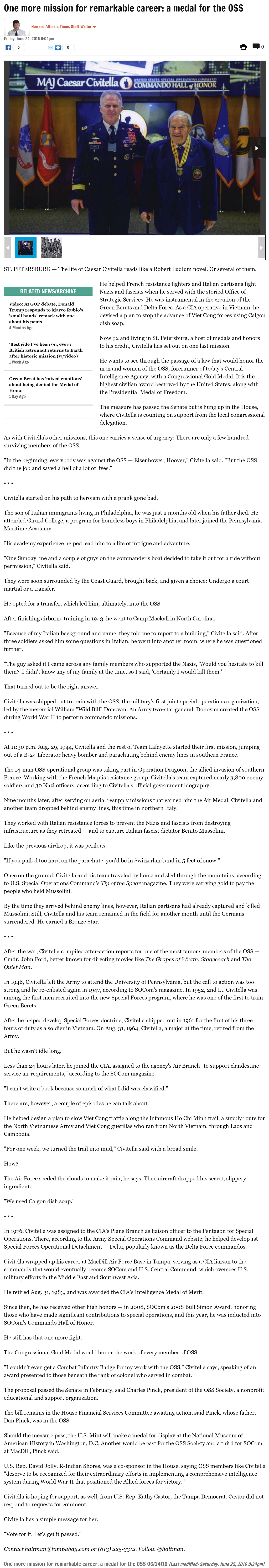

PHOTO: Shown with Gen. Raymond “Tony” Thomas III, commander of SOCom at MacDill Air Force Base, Caesar Civitella, right, was inducted into SOCom’s Commando Hall of Honor this year. Courtesy of Caesar Civitella

ST. PETERSBURG — The life of Caesar Civitella reads like a Robert Ludlum novel. Or several of them.

He helped French resistance fighters and Italian partisans fight Nazis and fascists when he served with the storied Office of Strategic Services. He was instrumental in the creation of the Green Berets and Delta Force. As a CIA operative in Vietnam, he devised a plan to stop the advance of Viet Cong forces using Calgon dish soap.

Now 92 and living in St. Petersburg, a host of medals and honors to his credit, Civitella has set out on one last mission.

He wants to see through the passage of a law that would honor the men and women of the OSS, forerunner of today’s Central Intelligence Agency, with a Congressional Gold Medal. It is the highest civilian award bestowed by the United States, along with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The measure has passed the Senate but is hung up in the House, where Civitella is counting on support from the local congressional delegation.

As with Civitella’s other missions, this one carries a sense of urgency: There are only a few hundred surviving members of the OSS.

“In the beginning, everybody was against the OSS — Eisenhower, Hoover,” Civitella said. “But the OSS did the job and saved a hell of a lot of lives.”

Civitella started on his path to heroism with a prank gone bad.

The son of Italian immigrants living in Philadelphia, he was just 2 months old when his father died. He attended Girard College, a program for homeless boys in Philadelphia, and later joined the Pennsylvania Maritime Academy.

His academy experience helped lead him to a life of intrigue and adventure.

“One Sunday, me and a couple of guys on the commander’s boat decided to take it out for a ride without permission,” Civitella said.

They were soon surrounded by the Coast Guard, brought back, and given a choice: Undergo a court martial or a transfer.

He opted for a transfer, which led him, ultimately, into the OSS.

After finishing airborne training in 1943, he went to Camp Mackall in North Carolina.

“Because of my Italian background and name, they told me to report to a building,” Civitella said. After three soldiers asked him some questions in Italian, he went into another room, where he was questioned further.

“The guy asked if I came across any family members who supported the Nazis, ‘Would you hesitate to kill them?’ I didn’t know any of my family at the time, so I said, ‘Certainly I would kill them.’ “

That turned out to be the right answer.

Civitella was shipped out to train with the OSS, the military’s first joint special operations organization, led by the mercurial William “Wild Bill” Donovan. An Army two-star general, Donovan created the OSS during World War II to perform commando missions.

At 11:30 p.m. Aug. 29, 1944, Civitella and the rest of Team Lafayette started their first mission, jumping out of a B-24 Liberator heavy bomber and parachuting behind enemy lines in southern France.

The 14-man OSS operational group was taking part in Operation Dragoon, the allied invasion of southern France. Working with the French Maquis resistance group, Civitella’s team captured nearly 3,800 enemy soldiers and 30 Nazi officers, according to Civitella’s official government biography.

Nine months later, after serving on aerial resupply missions that earned him the Air Medal, Civitella and another team dropped behind enemy lines, this time in northern Italy.

They worked with Italian resistance forces to prevent the Nazis and fascists from destroying infrastructure as they retreated — and to capture Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

Like the previous airdrop, it was perilous.

“If you pulled too hard on the parachute, you’d be in Switzerland and in 5 feet of snow.”

Once on the ground, Civitella and his team traveled by horse and sled through the mountains, according to U.S. Special Operations Command’s Tip of the Spear magazine. They were carrying gold to pay the people who held Mussolini.

By the time they arrived behind enemy lines, however, Italian partisans had already captured and killed Mussolini. Still, Civitella and his team remained in the field for another month until the Germans surrendered. He earned a Bronze Star.

After the war, Civitella compiled after-action reports for one of the most famous members of the OSS — Cmdr. John Ford, better known for directing movies like The Grapes of Wrath, Stagecoach and The Quiet Man.

In 1946, Civitella left the Army to attend the University of Pennsylvania, but the call to action was too strong and he re-enlisted again in 1947, according to SOCom’s magazine. In 1952, 2nd Lt. Civitella was among the first men recruited into the new Special Forces program, where he was one of the first to train Green Berets.

After he helped develop Special Forces doctrine, Civitella shipped out in 1961 for the first of his three tours of duty as a soldier in Vietnam. On Aug. 31, 1964, Civitella, a major at the time, retired from the Army.

But he wasn’t idle long.

Less than 24 hours later, he joined the CIA, assigned to the agency’s Air Branch “to support clandestine service air requirements,” according to the SOCom magazine.

“I can’t write a book because so much of what I did was classified.”

There are, however, a couple of episodes he can talk about.

He helped design a plan to slow Viet Cong traffic along the infamous Ho Chi Minh trail, a supply route for the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong guerillas who ran from North Vietnam, through Laos and Cambodia.

“For one week, we turned the trail into mud,” Civitella said with a broad smile.

How?

The Air Force seeded the clouds to make it rain, he says. Then aircraft dropped his secret, slippery ingredient.

“We used Calgon dish soap.”

In 1976, Civitella was assigned to the CIA’s Plans Branch as liaison officer to the Pentagon for Special Operations. There, according to the Army Special Operations Command website, he helped develop 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment — Delta, popularly known as the Delta Force commandos.

Civitella wrapped up his career at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, serving as a CIA liaison to the commands that would eventually become SOCom and U.S. Central Command, which oversees U.S. military efforts in the Middle East and Southwest Asia.

He retired Aug. 31, 1983, and was awarded the CIA’s Intelligence Medal of Merit.

Since then, he has received other high honors — in 2008, SOCom’s 2008 Bull Simon Award, honoring those who have made significant contributions to special operations, and this year, he was inducted into SOCom’s Commando Hall of Honor.

He still has that one more fight.

The Congressional Gold Medal would honor the work of every member of OSS.

“I couldn’t even get a Combat Infantry Badge for my work with the OSS,” Civitella says, speaking of an award presented to those beneath the rank of colonel who served in combat.

The proposal passed the Senate in February, said Charles Pinck, president of the OSS Society, a nonprofit educational and support organization.

The bill remains in the House Financial Services Committee awaiting action, said Pinck, whose father, Dan Pinck, was in the OSS.

Should the measure pass, the U.S. Mint will make a medal for display at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Another would be cast for the OSS Society and a third for SOCom at MacDill, Pinck said.

U.S. Rep. David Jolly, R-Indian Shores, was a co-sponsor in the House, saying OSS members like Civitella “deserve to be recognized for their extraordinary efforts in implementing a comprehensive intelligence system during World War II that positioned the Allied forces for victory.”

Civitella is hoping for support, as well, from U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor, the Tampa Democrat. Castor did not respond to requests for comment.

Civitella has a simple message for her.

“Vote for it. Let’s get it passed.”

Wayback image