TAMPA — From chasing drug smugglers who use submarines to the latest wave of warfare playing out over the skies of Ukraine, Sarasota inventor Skip Parish has a solution.

Drones.

Parish, who works with the Australian firm Unmanned Aerial Technologies, just got back from Ukraine, where he met with military and industrial officials to learn tactical techniques and discussed ways of developing defensive measures for drones with Ukrainian industry.

And this weekend, Parish, along with the staff of Hann Powerboats of Sarasota, is scheduled to meet with officials from Panama to discuss selling a combined fast boat-drone package that will help that nation stop the transport of cocaine and other illegal drugs.

“This technology is a whole new tactical way of doing things,” Parish said. “I call it a sea change.”

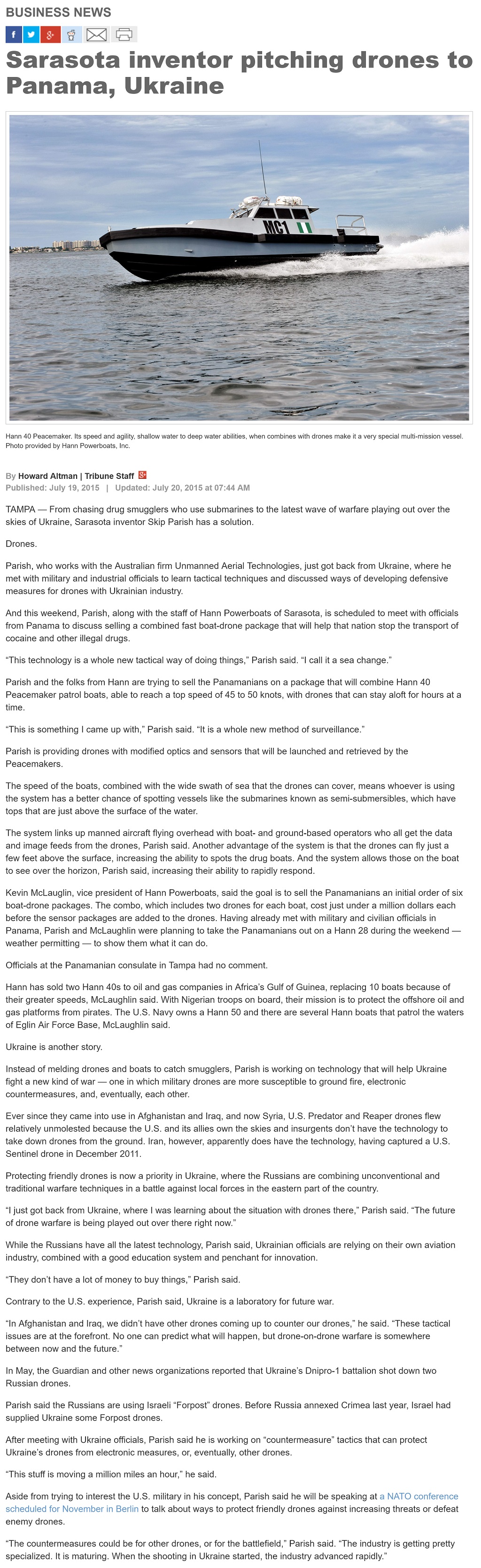

Parish and the folks from Hann are trying to sell the Panamanians on a package that will combine Hann 40 Peacemaker patrol boats, able to reach a top speed of 45 to 50 knots, with drones that can stay aloft for hours at a time.

“This is something I came up with,” Parish said. “It is a whole new method of surveillance.”

Parish is providing drones with modified optics and sensors that will be launched and retrieved by the Peacemakers.

The speed of the boats, combined with the wide swath of sea that the drones can cover, means whoever is using the system has a better chance of spotting vessels like the submarines known as semi-submersibles, which have tops that are just above the surface of the water.

The system links up manned aircraft flying overhead with boat- and ground-based operators who all get the data and image feeds from the drones, Parish said. Another advantage of the system is that the drones can fly just a few feet above the surface, increasing the ability to spots the drug boats. And the system allows those on the boat to see over the horizon, Parish said, increasing their ability to rapidly respond.

Kevin McLauglin, vice president of Hann Powerboats, said the goal is to sell the Panamanians an initial order of six boat-drone packages. The combo, which includes two drones for each boat, cost just under a million dollars each before the sensor packages are added to the drones. Having already met with military and civilian officials in Panama, Parish and McLaughlin were planning to take the Panamanians out on a Hann 28 during the weekend — weather permitting — to show them what it can do.

Officials at the Panamanian consulate in Tampa had no comment.

Hann has sold two Hann 40s to oil and gas companies in Africa’s Gulf of Guinea, replacing 10 boats because of their greater speeds, McLaughlin said. With Nigerian troops on board, their mission is to protect the offshore oil and gas platforms from pirates. The U.S. Navy owns a Hann 50 and there are several Hann boats that patrol the waters of Eglin Air Force Base, McLaughlin said.

Ukraine is another story.

Instead of melding drones and boats to catch smugglers, Parish is working on technology that will help Ukraine fight a new kind of war — one in which military drones are more susceptible to ground fire, electronic countermeasures, and, eventually, each other.

Ever since they came into use in Afghanistan and Iraq, and now Syria, U.S. Predator and Reaper drones flew relatively unmolested because the U.S. and its allies own the skies and insurgents don’t have the technology to take down drones from the ground. Iran, however, apparently does have the technology, having captured a U.S. Sentinel drone in December 2011.

Protecting friendly drones is now a priority in Ukraine, where the Russians are combining unconventional and traditional warfare techniques in a battle against local forces in the eastern part of the country.

“I just got back from Ukraine, where I was learning about the situation with drones there,” Parish said. “The future of drone warfare is being played out over there right now.”

While the Russians have all the latest technology, Parish said, Ukrainian officials are relying on their own aviation industry, combined with a good education system and penchant for innovation.

“They don’t have a lot of money to buy things,” Parish said.

Contrary to the U.S. experience, Parish said, Ukraine is a laboratory for future war.

“In Afghanistan and Iraq, we didn’t have other drones coming up to counter our drones,” he said. “These tactical issues are at the forefront. No one can predict what will happen, but drone-on-drone warfare is somewhere between now and the future.”

In May, the Guardian and other news organizations reported that Ukraine’s Dnipro-1 battalion shot down two Russian drones.

Parish said the Russians are using Israeli “Forpost” drones. Before Russia annexed Crimea last year, Israel had supplied Ukraine some Forpost drones.

After meeting with Ukraine officials, Parish said he is working on “countermeasure” tactics that can protect Ukraine’s drones from electronic measures, or, eventually, other drones.

“This stuff is moving a million miles an hour,” he said.

Aside from trying to interest the U.S. military in his concept, Parish said he will be speaking at a NATO conference scheduled for November in Berlin to talk about ways to protect friendly drones against increasing threats or defeat enemy drones.

“The countermeasures could be for other drones, or for the battlefield,” Parish said. “The industry is getting pretty specialized. It is maturing. When the shooting in Ukraine started, the industry advanced rapidly.”

PHOTO: Hann 40 Peacemaker. Its speed and agility, shallow water to deep water abilities, when combines with drones make it a very special multi-mission vessel. Photo provided by Hann Powerboats, Inc.