In the midst of the ceaseless flow of helicopters flying back and forth between the USS Midway and the besieged city of Saigon about 100 miles to the west, a small single-engine propeller plane appeared out of nowhere.

It was the morning of April 30, 1975 and unbeknownst to the men aboard the old aircraft carrier, Operation Frequent Wind, the frantic and chaotic effort to evacuate Saigon, was in its death throes as Communist forces were about overrun the South Vietnamese capital.

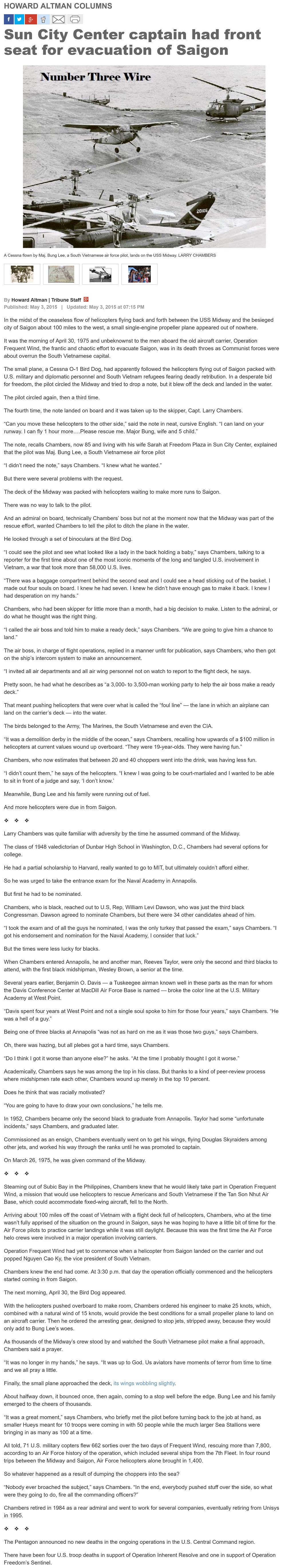

The small plane, a Cessna O-1 Bird Dog, had apparently followed the helicopters flying out of Saigon packed with U.S. military and diplomatic personnel and South Vietnam refugees fearing deadly retribution. In a desperate bid for freedom, the pilot circled the Midway and tried to drop a note, but it blew off the deck and landed in the water.

The pilot circled again, then a third time.

The fourth time, the note landed on board and it was taken up to the skipper, Capt. Larry Chambers.

“Can you move these helicopters to the other side,” said the note in neat, cursive English. “I can land on your runway. I can fly 1 hour more….Please rescue me. Major Bung, wife and 5 child.”

The note, recalls Chambers, now 85 and living with his wife Sarah at Freedom Plaza in Sun City Center, explained that the pilot was Maj. Bung Lee, a South Vietnamese air force pilot

“I didn’t need the note,” says Chambers. “I knew what he wanted.”

But there were several problems with the request.

The deck of the Midway was packed with helicopters waiting to make more runs to Saigon.

There was no way to talk to the pilot.

And an admiral on board, technically Chambers’ boss but not at the moment now that the Midway was part of the rescue effort, wanted Chambers to tell the pilot to ditch the plane in the water.

He looked through a set of binoculars at the Bird Dog.

“I could see the pilot and see what looked like a lady in the back holding a baby,” says Chambers, talking to a reporter for the first time about one of the most iconic moments of the long and tangled U.S. involvement in Vietnam, a war that took more than 58,000 U.S. lives.

“There was a baggage compartment behind the second seat and I could see a head sticking out of the basket. I made out four souls on board. I knew he had seven. I knew he didn’t have enough gas to make it back. I knew I had desperation on my hands.”

Chambers, who had been skipper for little more than a month, had a big decision to make. Listen to the admiral, or do what he thought was the right thing.

“I called the air boss and told him to make a ready deck,” says Chambers. “We are going to give him a chance to land.”

The air boss, in charge of flight operations, replied in a manner unfit for publication, says Chambers, who then got on the ship’s intercom system to make an announcement.

“I invited all air departments and all air wing personnel not on watch to report to the flight deck, he says.

Pretty soon, he had what he describes as “a 3,000- to 3,500-man working party to help the air boss make a ready deck.”

That meant pushing helicopters that were over what is called the “foul line” — the lane in which an airplane can land on the carrier’s deck — into the water.

The birds belonged to the Army, The Marines, the South Vietnamese and even the CIA.

“It was a demolition derby in the middle of the ocean,” says Chambers, recalling how upwards of a $100 million in helicopters at current values wound up overboard. “They were 19-year-olds. They were having fun.”

Chambers, who now estimates that between 20 and 40 choppers went into the drink, was having less fun.

“I didn’t count them,” he says of the helicopters. “I knew I was going to be court-martialed and I wanted to be able to sit in front of a judge and say, ‘I don’t know.’

Meanwhile, Bung Lee and his family were running out of fuel.

And more helicopters were due in from Saigon.

❖ ❖ ❖

Larry Chambers was quite familiar with adversity by the time he assumed command of the Midway.

The class of 1948 valedictorian of Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., Chambers had several options for college.

He had a partial scholarship to Harvard, really wanted to go to MIT, but ultimately couldn’t afford either.

So he was urged to take the entrance exam for the Naval Academy in Annapolis.

But first he had to be nominated.

Chambers, who is black, reached out to U.S, Rep, William Levi Dawson, who was just the third black Congressman. Dawson agreed to nominate Chambers, but there were 34 other candidates ahead of him.

“I took the exam and of all the guys he nominated, I was the only turkey that passed the exam,” says Chambers. “I got his endorsement and nomination for the Naval Academy, I consider that luck.”

But the times were less lucky for blacks.

When Chambers entered Annapolis, he and another man, Reeves Taylor, were only the second and third blacks to attend, with the first black midshipman, Wesley Brown, a senior at the time.

Several years earlier, Benjamin O. Davis — a Tuskeegee airman known well in these parts as the man for whom the Davis Conference Center at MacDill Air Force Base is named — broke the color line at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

“Davis spent four years at West Point and not a single soul spoke to him for those four years,” says Chambers. “He was a hell of a guy.”

Being one of three blacks at Annapolis “was not as hard on me as it was those two guys,” says Chambers.

Oh, there was hazing, but all plebes got a hard time, says Chambers.

“Do I think I got it worse than anyone else?” he asks. “At the time I probably thought I got it worse.”

Academically, Chambers says he was among the top in his class. But thanks to a kind of peer-review process where midshipmen rate each other, Chambers wound up merely in the top 10 percent.

Does he think that was racially motivated?

“You are going to have to draw your own conclusions,” he tells me.

In 1952, Chambers became only the second black to graduate from Annapolis. Taylor had some “unfortunate incidents,” says Chambers, and graduated later.

Commissioned as an ensign, Chambers eventually went on to get his wings, flying Douglas Skyraiders among other jets, and worked his way through the ranks until he was promoted to captain.

On March 26, 1975, he was given command of the Midway.

❖ ❖ ❖

Steaming out of Subic Bay in the Philippines, Chambers knew that he would likely take part in Operation Frequent Wind, a mission that would use helicopters to rescue Americans and South Vietnamese if the Tan Son Nhut Air Base, which could accommodate fixed-wing aircraft, fell to the North.

Arriving about 100 miles off the coast of Vietnam with a flight deck full of helicopters, Chambers, who at the time wasn’t fully apprised of the situation on the ground in Saigon, says he was hoping to have a little bit of time for the Air Force pilots to practice carrier landings while it was still daylight. Because this was the first time the Air Force helo crews were involved in a major operation involving carriers.

Operation Frequent Wind had yet to commence when a helicopter from Saigon landed on the carrier and out popped Nguyen Cao Ky, the vice president of South Vietnam.

Chambers knew the end had come. At 3:30 p.m. that day the operation officially commenced and the helicopters started coming in from Saigon.

The next morning, April 30, the Bird Dog appeared.

With the helicopters pushed overboard to make room, Chambers ordered his engineer to make 25 knots, which, combined with a natural wind of 15 knots, would provide the best conditions for a small propeller plane to land on an aircraft carrier. Then he ordered the arresting gear, designed to stop jets, stripped away, because they would only add to Bung Lee’s woes.

As thousands of the Midway’s crew stood by and watched the South Vietnamese pilot make a final approach, Chambers said a prayer.

“It was no longer in my hands,” he says. “It was up to God. Us aviators have moments of terror from time to time and we all pray a little.

Finally, the small plane approached the deck, its wings wobbling slightly.

About halfway down, it bounced once, then again, coming to a stop well before the edge. Bung Lee and his family emerged to the cheers of thousands.

“It was a great moment,” says Chambers, who briefly met the pilot before turning back to the job at hand, as smaller Hueys meant for 10 troops were coming in with 50 people while the much larger Sea Stallions were bringing in as many as 100 at a time.

All told, 71 U.S. military copters flew 662 sorties over the two days of Frequent Wind, rescuing more than 7,800, according to an Air Force history of the operation, which included several ships from the 7th Fleet. In four round trips between the Midway and Saigon, Air Force helicopters alone brought in 1,400.

So whatever happened as a result of dumping the choppers into the sea?

“Nobody ever broached the subject,” says Chambers. “In the end, everybody pushed stuff over the side, so what were they going to do, fire all the commanding officers?”

Chambers retired in 1984 as a rear admiral and went to work for several companies, eventually retiring from Unisys in 1995.

❖ ❖ ❖

The Pentagon announced no new deaths in the ongoing operations in the U.S. Central Command region.

There have been four U.S. troop deaths in support of Operation Inherent Resolve and one in support of Operation Freedom’s Sentinel.

PHOTO: A Cessna flown by Maj. Bung Lee, a South Vietnamese air force pilot, lands on the USS Midway. LARRY CHAMBERS