News / Military

Leaders at the command have said there is more to do in Syria and Afghanistan. But Trump wants troops out of Syria and reductions in Afghanistan.

By Howard Altman / Tampa Bay Times / December 26, 2018

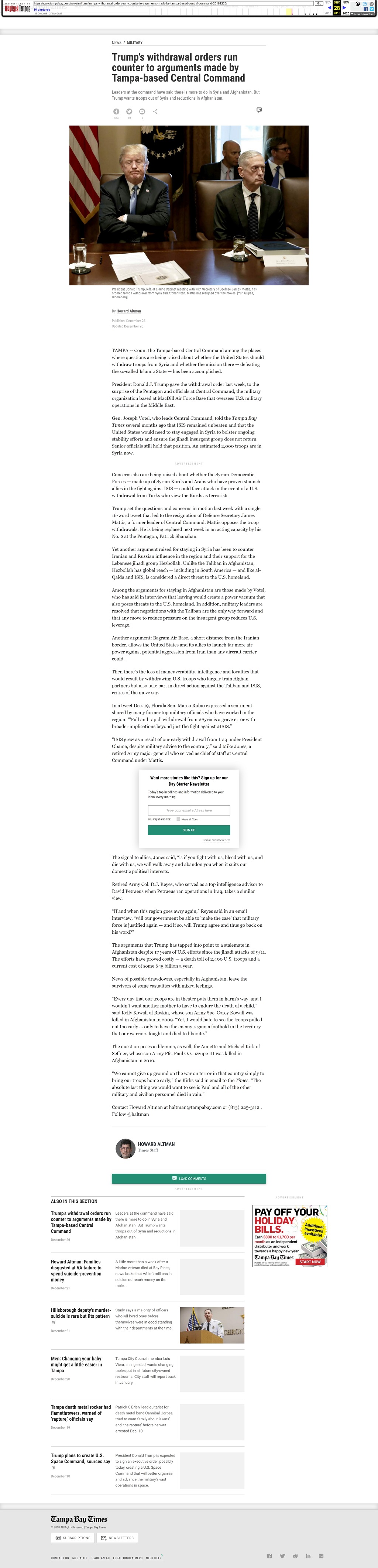

PHOTO: President Donald Trump, left, at a June Cabinet meeting with Secretary of Defense James Mattis, has ordered troops withdrawn from Syria and Afghanistan. Mattis has resigned over the moves. (Yuri Gripas, Bloomberg)

TAMPA — Count the Tampa-based Central Command among the places where questions are being raised about whether the United States should withdraw troops from Syria and whether the mission there — defeating the so-called Islamic State — has been accomplished.

President Donald J. Trump gave the withdrawal order last week, to the surprise of the Pentagon and officials at Central Command, the military organization based at MacDill Air Force Base that oversees U.S. military operations in the Middle East.

Gen. Joseph Votel, who leads Central Command, told the Tampa Bay Times several months ago that ISIS remained unbeaten and that the United States would need to stay engaged in Syria to bolster ongoing stability efforts and ensure the jihadi insurgent group does not return. Senior officials still hold that position. An estimated 2,000 troops are in Syria now.

Concerns also are being raised about whether the Syrian Democratic Forces — made up of Syrian Kurds and Arabs who have proven staunch allies in the fight against ISIS — could face attack in the event of a U.S. withdrawal from Turks who view the Kurds as terrorists.

Trump set the questions and concerns in motion last week with a single 16-word tweet that led to the resignation of Defense Secretary James Mattis, a former leader of Central Command. Mattis opposes the troop withdrawals. He is being replaced next week in an acting capacity by his No. 2 at the Pentagon, Patrick Shanahan.

Yet another argument raised for staying in Syria has been to counter Iranian and Russian influence in the region and their support for the Lebanese jihadi group Hezbollah. Unlike the Taliban in Afghanistan, Hezbollah has global reach — including in South America — and like al-Qaida and ISIS, is considered a direct threat to the U.S. homeland.

Among the arguments for staying in Afghanistan are those made by Votel, who has said in interviews that leaving would create a power vacuum that also poses threats to the U.S. homeland. In addition, military leaders are resolved that negotiations with the Taliban are the only way forward and that any move to reduce pressure on the insurgent group reduces U.S. leverage.

Another argument: Bagram Air Base, a short distance from the Iranian border, allows the United States and its allies to launch far more air power against potential aggression from Iran than any aircraft carrier could.

Then there’s the loss of maneuverability, intelligence and loyalties that would result by withdrawing U.S. troops who largely train Afghan partners but also take part in direct action against the Taliban and ISIS, critics of the move say.

In a tweet Dec. 19, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio expressed a sentiment shared by many former top military officials who have worked in the region: “‘Full and rapid’ withdrawal from #Syria is a grave error with broader implications beyond just the fight against #ISIS.”

“ISIS grew as a result of our early withdrawal from Iraq under President Obama, despite military advice to the contrary,” said Mike Jones, a retired Army major general who served as chief of staff at Central Command under Mattis.

The signal to allies, Jones said, “is if you fight with us, bleed with us, and die with us, we will walk away and abandon you when it suits our domestic political interests.

Retired Army Col. D.J. Reyes, who served as a top intelligence advisor to David Petraeus when Petraeus ran operations in Iraq, takes a similar view.

“If and when this region goes awry again,” Reyes said in an email interview, “will our government be able to ‘make the case’ that military force is justified again — and if so, will Trump agree and thus go back on his word?”

The arguments that Trump has tapped into point to a stalemate in Afghanistan despite 17 years of U.S. efforts since the jihadi attacks of 9/11. The efforts have proved costly — a death toll of 2,400 U.S. troops and a current cost of some $45 billion a year.

News of possible drawdowns, especially in Afghanistan, leave the survivors of some casualties with mixed feelings.

“Every day that our troops are in theater puts them in harm’s way, and I wouldn’t want another mother to have to endure the death of a child,” said Kelly Kowall of Ruskin, whose son Army Spc. Corey Kowall was killed in Afghanistan in 2009. “Yet, I would hate to see the troops pulled out too early … only to have the enemy regain a foothold in the territory that our warriors fought and died to liberate.”

The question poses a dilemma, as well, for Annette and Michael Kirk of Seffner, whose son Army Pfc. Paul O. Cuzzupe III was killed in Afghanistan in 2010.

“We cannot give up ground on the war on terror in that country simply to bring our troops home early,” the Kirks said in email to the Times. “The absolute last thing we would want to see is Paul and all of the other military and civilian personnel died in vain.”

Wayback image