News / Weather

By Howard Altman / Tampa Bay Times / September 1, 2016

VIDEO: (missing)

As Hermine spins slowly northeast, weather scientists sort through computer data aboard a plane that shudders through savage blasts from the storm.

Todd Richards slides a cylinder known as a dropsonde into the tube behind him, and with a whoosh, it flies out of the airplane, gathering data during its short plunge toward the Gulf of Mexico a mile below.

It is Wednesday evening just before dark aboard the Orion WP-3D Hurricane Hunter airplane, a four-engine turboprop based at MacDill Air Force Base and known as Miss Piggy.

A dropsonde reading three hours earlier showed wind speeds of around 45 mph, enough for the National Hurricane Center in Miami to declare Hermine a tropical storm.

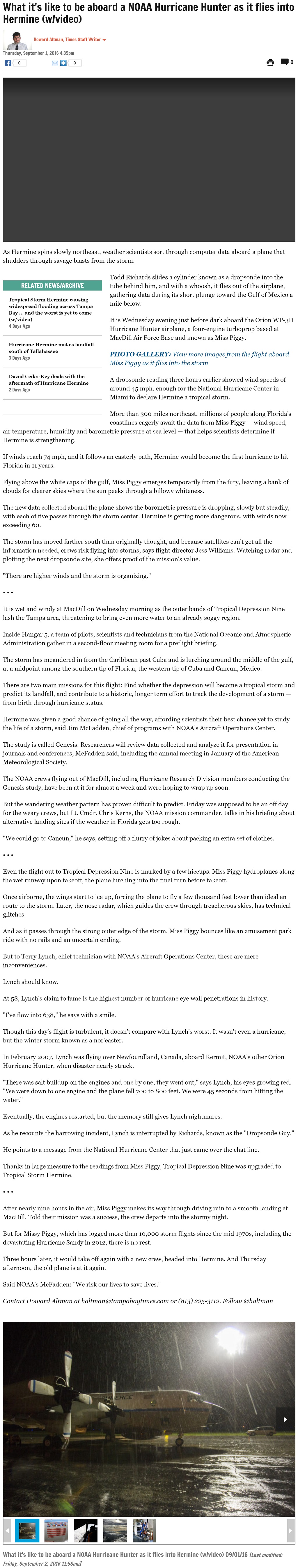

More than 300 miles northeast, millions of people along Florida’s coastlines eagerly await the data from Miss Piggy — wind speed, air temperature, humidity and barometric pressure at sea level — that helps scientists determine if Hermine is strengthening.

If winds reach 74 mph, and it follows an easterly path, Hermine would become the first hurricane to hit Florida in 11 years.

Flying above the white caps of the gulf, Miss Piggy emerges temporarily from the fury, leaving a bank of clouds for clearer skies where the sun peeks through a billowy whiteness.

The new data collected aboard the plane shows the barometric pressure is dropping, slowly but steadily, with each of five passes through the storm center. Hermine is getting more dangerous, with winds now exceeding 60.

The storm has moved farther south than originally thought, and because satellites can’t get all the information needed, crews risk flying into storms, says flight director Jess Williams. Watching radar and plotting the next dropsonde site, she offers proof of the mission’s value.

“There are higher winds and the storm is organizing.”

It is wet and windy at MacDill on Wednesday morning as the outer bands of Tropical Depression Nine lash the Tampa area, threatening to bring even more water to an already soggy region.

Inside Hangar 5, a team of pilots, scientists and technicians from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration gather in a second-floor meeting room for a preflight briefing.

The storm has meandered in from the Caribbean past Cuba and is lurching around the middle of the gulf, at a midpoint among the southern tip of Florida, the western tip of Cuba and Cancun, Mexico.

There are two main missions for this flight: Find whether the depression will become a tropical storm and predict its landfall, and contribute to a historic, longer term effort to track the development of a storm — from birth through hurricane status.

Hermine was given a good chance of going all the way, affording scientists their best chance yet to study the life of a storm, said Jim McFadden, chief of programs with NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center.

The study is called Genesis. Researchers will review data collected and analyze it for presentation in journals and conferences, McFadden said, including the annual meeting in January of the American Meteorological Society.

The NOAA crews flying out of MacDill, including Hurricane Research Division members conducting the Genesis study, have been at it for almost a week and were hoping to wrap up soon.

But the wandering weather pattern has proven difficult to predict. Friday was supposed to be an off day for the weary crews, but Lt. Cmdr. Chris Kerns, the NOAA mission commander, talks in his briefing about alternative landing sites if the weather in Florida gets too rough.

“We could go to Cancun,” he says, setting off a flurry of jokes about packing an extra set of clothes.

Even the flight out to Tropical Depression Nine is marked by a few hiccups. Miss Piggy hydroplanes along the wet runway upon takeoff, the plane lurching into the final turn before takeoff.

Once airborne, the wings start to ice up, forcing the plane to fly a few thousand feet lower than ideal en route to the storm. Later, the nose radar, which guides the crew through treacherous skies, has technical glitches.

And as it passes through the strong outer edge of the storm, Miss Piggy bounces like an amusement park ride with no rails and an uncertain ending.

But to Terry Lynch, chief technician with NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center, these are mere inconveniences.

Lynch should know.

At 58, Lynch’s claim to fame is the highest number of hurricane eye wall penetrations in history.

“I’ve flow into 638,” he says with a smile.

Though this day’s flight is turbulent, it doesn’t compare with Lynch’s worst. It wasn’t even a hurricane, but the winter storm known as a nor’easter.

In February 2007, Lynch was flying over Newfoundland, Canada, aboard Kermit, NOAA’s other Orion Hurricane Hunter, when disaster nearly struck.

“There was salt buildup on the engines and one by one, they went out,” says Lynch, his eyes growing red. “We were down to one engine and the plane fell 700 to 800 feet. We were 45 seconds from hitting the water.”

Eventually, the engines restarted, but the memory still gives Lynch nightmares.

As he recounts the harrowing incident, Lynch is interrupted by Richards, known as the “Dropsonde Guy.”

He points to a message from the National Hurricane Center that just came over the chat line.

Thanks in large measure to the readings from Miss Piggy, Tropical Depression Nine was upgraded to Tropical Storm Hermine.

After nearly nine hours in the air, Miss Piggy makes its way through driving rain to a smooth landing at MacDill. Told their mission was a success, the crew departs into the stormy night.

But for Missy Piggy, which has logged more than 10,000 storm flights since the mid 1970s, including the devastating Hurricane Sandy in 2012, there is no rest.

Three hours later, it would take off again with a new crew, headed into Hermine. And Thursday afternoon, the old plane is at it again.

Said NOAA’s McFadden: “We risk our lives to save lives.”

- Photo 1: After the end of a reconnaissance flight Wednesday, a Hurricane Hunter airplane shuts down at MacDill Air Force Base. Crews rotate in and out, but the four-engine turboprop takes off again three hours later. (LUIS SANTANA | Times)

- Photo 2: Stickers and flags on the fuselage of the NOAA Hurricane Hunter WP-3 Orion show the storms and countries that Miss Piggy has flown through. Millions of people depend on data from the flights. (LUIS SANTANA | Times)

- Photo 3: Stickers and flags on the fuselage of the NOAA Hurricane Hunter WP-3 Orion show the storms and countries that Miss Piggy has flown through. Millions of people depend on data from the flights. (LUIS SANTANA | Times)

- Photo 4: NOAA’s hurricane hunter flight made five passes in and out of the tropical depression Wednesday, emerging at one point to a scenic sunset over the Gulf of Mexico. (LUIS SANTANA | Times)

- Photo 5: NOAA technician Todd Richards prepares to send off a sophisticated module called a dropsonde that will gather data as it plunges toward the Gulf of Mexico. Data collected aboard the plane showed the barometric pressure dropping with each of five passes through the storm center. (LUIS SANTANA | Times)

Wayback image